by pirxthepilot » Wed Nov 26, 2014 6:11 pm

by pirxthepilot » Wed Nov 26, 2014 6:11 pm

good profile from the new yorker here.

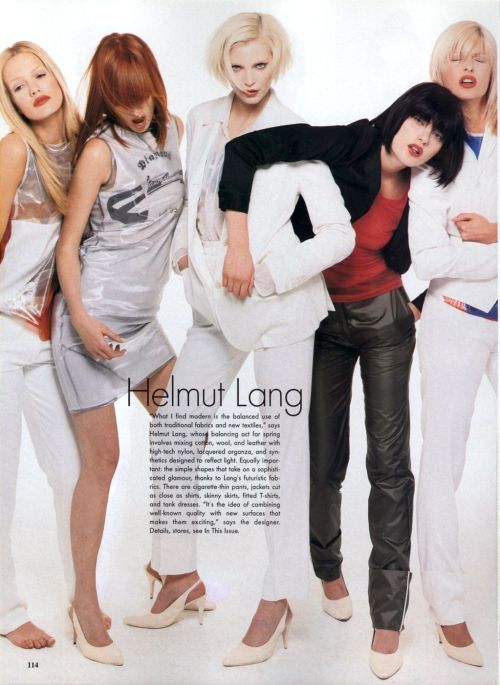

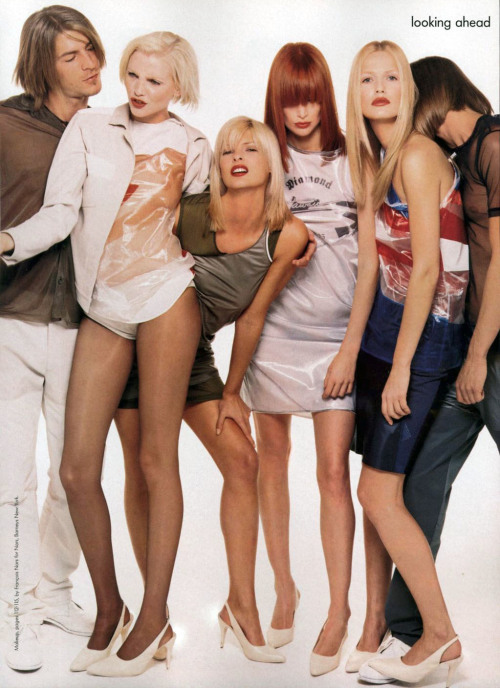

The Invisible Designer: Helmut Lang

From The New Yorker

September 18, 2000

About four years ago, in a men's store called Camouflage, in Chelsea, I tried on some trousers. They were perfectly ordinary-looking thin-wale corduroys, and yet something about them was different: the fabric was softer, the color was slightly subtler than basic black. The pants were unpleated, the rise was high, the leg slim. There was a loop for the button over the rear pocket, and an inner waist button-details you don't often find on sportswear. Was this fashion? Perhaps, but it was hidden; only I would know. The label was inside, too, small and not at all logomaniacal--just the words "Helmut Lang" in black on white. It seemed intended to evoke the "tickets" you find inside bespoke suits from made-to-measure tailors. The pants cost a hundred and twenty dollars--not bad, as designer clothes go. I bought them.

This encounter occurred during my quest to shed the preppy uniforms I'd been wearing in the fifteen years since college--a tux for formal occasions, a suit for church and funerals, a blue blazer and tailored slacks for looking "smart," a polo shirt and khakis for going out on weekends--and to find a more casual style, one that was better suited to the identity I was imagining for myself. (Clothes, of course, are not so much about who you are as who you want to be.) I had discovered the melancholy truth that men everywhere have learned as they try to master the new casual style at the office: dressing casually actually requires that a man take fashion more seriously than dressing formally does. The new casual, like the old casual, is supposed to give an appearance of ease, of comfort with yourself. But, unlike the old casual, the new casual is all about status. "Casual Power," a recent style guide by Sherry Maysonave, describes a hierarchy with six different levels of casual attire: Active Casual, Rugged Casual (also called "outdoorsy"), Sporty Casual, Smart Casual (or "snappy"), Dressy Casual, and Business Casual. This may be the most depressing thing about the casual movement: no clothing is casual anymore.

Helmut Lang, the Austrian-born designer, seemed to understand exactly what I needed--a uniform for the new casual world. I bought some more of his clothes: a ribbed cotton sweater that didn't stretch like my other cotton sweaters; a few pairs of khakis, which had a pleasingly crisp finish; a denim shirt; a woollen sweater in a beautiful straw color; and a pair of jeans. They were intelligent clothes, designed for a maximum number of situations, both work and play, which increasingly seem to be performed in the same outfits.

But there was also a deceptive aspect to my new uniforms. They appeared to be casual, but they were not, and I knew they weren't. The designer seemed to be playing off this stealthy quality by hiding certain nonfunctional fashion elements inside the clothes, such as the faux drawstrings inside the waistband of otherwise totally ordinary chinos. This hidden streak extends to the way the clothes are presented. The Helmut Lang store in SoHo, which was designed in close collaboration with Richard Gluckman, a New York-based architect of galleries and museums, violates the most basic principle of retail design: you are supposed to be able to see the merchandise. Here the clothes are concealed from view when you walk in--enclosed inside alcoves in the middle of the store. Hiding, it seems, is part of who Helmut Lang is.

Hoping for a glimpse of the man whose name was inside my clothes, I attended this year's American Fashion Awards, which took place at Lincoln Center in June. Polly Mellen, a longtime arbiter of American fashion, was at a buffet supper preceding the awards, scanning the big white tent for that sleek, seal-like shape that she said she found so enchanting-Helmut Lang's head. "Where are you, Helmut, where are you?" she called out. "You are our glamour boy. You have to come."

Lang, who is forty-three years old, had been nominated for all three of the evening's major awards--for womenswear, menswear, and accessories--an honor never before bestowed on any designer. He moved his business from Paris to New York in 1997, and this spring he joined the Council of Fashion Designers of America. The C.F.D.A., which organized the awards ceremony, was happy to count as one of its own the designer whose utilitarian, austere, sportswear-inspired aesthetic was widely copied during the nineties, and became the dominant style of the decade: minimalism. These honors were a way of recognizing his influence, which is likely to increase--Lang recently formed a partnership with the Prada Group--as well as a way of welcoming him to the club.

Tommy Hilfiger was in the tent, shaking hands and flashing his toothy, sideways grin. ChloÎ Sevigny came in wearing a Helmut Lang organza skirt. Elizabeth Hurley and Claudia Schiffer appeared, looking very eighties, both in gorgeous, shimmery Valentino gowns with ruffles around the bosom. There is nothing restrained about Valentino--elegance and beauty come before comfort and function. "Too fussy," pronounced Polly Mellen, continuing her search for Helmut Lang.

But Lang was nowhere to be found. It seemed he had decided to stay in his SoHo headquarters, where he was working on his spring, 2001, menswear collection. (Fern Mallis, the C.F.D.A.'s executive director, received word from Lang's P.R. agency about an hour before the event began, and said she was "flabbergasted.") As the news spread that Lang was not going to appear at the party, the festive spirit began to leak out of the tent. There was a feeling that Lang might not want to be a member of the club, after all.

Lang lost the first big award of the evening, Accessory Designer of the Year, which went to the team of Richard Lambertson and John Truex. But he won the next one--Menswear Designer of the Year. When his name was announced, many in the audience, not yet aware of his absence, expected a rare sighting of the man himself, and there was an audible groan as Ingrid Sischy, the editor-in-chief of Interview, appeared out of the darkness and mounted the podium, where she solemnly accepted the award for Lang, whom she thanked for "changing the rules in American fashion." The line did not go over well with the crowd, which included most of the rulemakers. (Cathy Horyn, the Times fashion critic, was sitting next to Oscar de la Renta and his entourage, and later wrote that de la Renta repeated "Changed American fashion?" in an incredulous tone.)

The competition for the evening's most prestigious award, Womenswear Designer of the Year, was widely thought to be between de la Renta, who first achieved fame as a society designer in the eighties, and Lang. (The third nominee was Donna Karan.) It was a contest between excess and restraint. When de la Renta won, to wild cheering, it seemed like another sign that the eighties were back in business.

There was a feeling among the people I spoke to after the awards that this time Helmut had gone too far. "We all have to do things we don't want to do sometimes," said AndrÈ Leon Talley, the editor-at-large of Vogue. Anna Wintour described Helmut's decision as "a mistake." "If he had been out of the country, maybe, but he was just downtown. I realize he was working," she said, with mock reverence. (Part of the mystique that surrounds Lang derives from the intensity with which he approaches his work, and his Germanic attention to detail. He works "like a wild man," says the artist Jenny Holzer, his friend and sometime collaborator.) Still, Wintour went on, "If I had known he wasn't coming, I would have called him. It was discourteous not to turn up."

Lang has annoyed the American fashion community before by violating the protocol. He has rebelled against the onerous schedule of runway presentations, the four yearly spectacles (two each for the men's and women's lines) at which designers are supposed to submit new work to the scrutiny of the press and of the buyers from the big department stores. Lang shows his men's clothes together with his women's, but even this seems too much for him. (He calls his presentations not collections but sÈances de travail--working sessions.) A week before his fall-winter 1998, show, Lang decided to cancel his runway presentation and show pictures of his clothes on the Internet instead. Fashion editors were given CD-roms.

Fashion people love to use the word "modern" to justify the latest trend, but the fashion industry is quite unmodern, and becoming steadily more so as its old top-down hierarchy falls farther and farther out of touch with the casual-all-year-long world we live in. The collections are about display, and Helmut Lang has a deep aversion to display.

It runs through everything he does, from his minimalism to his conspicuous absence from the American Fashion Awards. This is the way in which Lang really is trying to change the rules--to make fashion less about creating a spectacle for the press and more about the problem most people face when they think of fashion, which is simply what to put on in the morning.

If you go into the Helmut Lang store on Greene Street, you will see four racks of clothing, two of men's and two of women's. The least expensive clothes in the store, T-shirts and jeans, often hang next to the most expensive items, silk and chiffon dresses and shearling coats. Most designers are careful to keep their high-priced, more formal clothes separate from their lower-priced casual wear. Armani, for example, has an expensive Giorgio Armani line, a sportswear-oriented Emporio Armani line, and a casual A/X Armani Exchange line. Lang has only one line, Helmut Lang, and instead of diversifying as his business grows, he is doing the opposite--his short-lived Helmut Lang Jeans line was recently reabsorbed into the parent.

Lang's mixing of the casual and the formal is not just a matter of marketing; it goes to the core of his aesthetic. His most expensive formal clothes have the ease and simplicity of everyday stuff, and his casual clothes have the correctness and detailing of ready-to-wear. Most high-fashion designers, whose natural leanings are toward ornament and glamour, don't do casual clothes very well--the fabric is too rich, the styling too elaborate. But Lang's distinction as a designer is his instinct for the appeal of the most basic items, like an old blue sweatshirt or a T-shirt worn silky with use, and he has created a whole new genre of luxury casual clothes. According to Katherine Betts, the editor-in-chief of Harper's Bazaar, "Lang did for T-shirts and jeans what Ralph Lauren did for club ties and tweed jackets--he made them fashion garments."

This transformation, the making of fashion out of everyday clothes, is a sleight of hand that involves more than just design. It is also a matter of the designer's image: the idea that the brand name conveys. The great couturiers, like Coco Chanel and Christian Dior, stood for the idea of high fashion--an Èlite enterprise that only the rich could afford. Then came the Italian fashion princes, like Armani and Gianni Versace, who used their own media celebrity to give ready-to-wear clothes the kind of allure that made-to-measure clothes used to have. One cannot see their names without thinking of their faces: fit and bronzed Italian men, relaxing in their villas, attractive in a way that made the clothes attractive. Then came Ralph Lauren, who used "life-style marketing"--associating his clothes with upper-middle-class Americans--to create a new kind of fashion image. Lauren's face was an inescapable part of the image--tanned, smiling, somewhere-out-there-on-the-range Ralph.

What does Helmut Lang stand for? It's not the idea of high fashion, nor is it any one particular life style, nor is it the personal fabulousness of Lang himself. There is no picture of Helmut Lang to go with the name--a rarity in our visual, celebrity-conscious culture--and he almost never uses models in his ads. Often the ads don't even show his clothes: you just see the words "Helmut Lang." But this is precisely what makes Lang appealing: his name seems to stand for something more than just clothes. "When you hear the name Helmut Lang, you think of technology, of fabric, of movement, not just pants and skirts," Jeffrey Kalinsky, the owner of Jeffrey, a boutique in lower Manhattan, says. If Lang's image has any precedent, it is in the avant-garde fashion brands, like Costume National, the Italian line designed by Ennio Capasa, or Comme des GarÁons, the French company that the Japanese-born Rei Kawakubo designs for--companies that represent innovation, intelligent design, and an independent spirit. Lang's association with the art world--he has collaborated with Louise Bourgeois and Jenny Holzer--has also given his name the kind of artistic integrity that famous architects frequently enjoy, but fashion designers seldom do.

All of which makes Lang's decision, last year, to sell a fifty-one-per-cent stake of his company to the Prada Group somewhat perplexing. Prada has established itself as a major brand largely by mining the appeal of esoteric fashion and figuring out a way to make big business out of it. Faye I. Landes, a retailing analyst with the investment firm of Sanford C. Bernstein, told me, "What Prada is better at than anyone is taking avant-garde fashion and making it palatable for both starlets and ordinary people."

Led by Patrizio Bertelli, the husband of Miuccia Prada, the firm's chief clothing designer, the Prada Group has built up three of its own brands (Miu Miu, Prada Sport, and Prada) by carefully mixing the cutting edge with the classic. In the last six months of 1999, it consolidated its position as a leading luxury conglomerate by acquiring--in addition to a share of Helmut Lang--Jil Sander, the company run by its namesake, a German-born designer who shares Lang's minimalist approach; Church's, the English shoemaker; and fifty-one per cent of Fendi, together with LVMH MoÎt Hennessy Louis Vuitton. Prada's blending of art and commerce has not been entirely smooth. Jil Sander's relationship with Prada went sour quickly, causing her to quit only five months after selling her company. (Having given up the rights to her name, she is currently not designing anywhere.)

Under the terms of the deal with Lang, Prada runs the business side of the operation, which includes distribution and manufacturing, and Lang retains control of design and advertising. Prada has developed a line of Helmut Lang accessories--shoes, bags, belts, wallets, eyewear, and luggage. Helmut Lang stores have opened in Hong Kong and Singapore, and are under construction in Tokyo and Kobe, and there are plans to open stores in London, Paris, and Los Angeles. In addition to all this Prada-led expansion, Procter & Gamble launched a complete line of Helmut Lang scents in May, and at the end of September a perfumery will open across the street from his flagship store, on Greene Street. There is talk of a new line of Helmut Lang cosmetics, possibly followed by Helmut Lang housewares. He may be a minimalist, but he wants to be a big minimalist.

One question this rapid expansion raises is to what extent Lang's image can retain its mystique if the designer himself becomes overexposed. Look at what happened to Tommy Hilfiger: his stock price lost almost half its value in the past year, as Tommy came to seem more like a brand manager than a designer. One might also ask how Lang, who has consistently gone against the prevailing current in fashion--whatever it may be--can maintain his independence under Prada. Ennio Capasa, of Costume National, told me recently that he did not see how a serious designer could sell to Prada and stay "authentic." "And if you are no longer authentic, what is the point?"

Lang's face changes, depending on how you look at him. From the front, he looks almost conventionally handsome: his forehead high and clear, and his eyes squinting at just the right French-movie-star angle of cool--there is something lively, almost merry, in them. But in profile he appears tortured, his eyes darting from under the hooded flesh at the corners, his mouth turned down at the edges.

I met Lang for the first time the day after the American Fashion Awards. Our initial meeting had been cancelled several times, so I expected this appointment to be cancelled, too; Lang, it seems, doesn't divide up his day in an orderly manner, but works intuitively, making of his schedule a raft of different possible commitments and deadlines and ideas, all awaiting the arrival of what he likes to call "the right organic moment." It appeared that our right organic moment had arrived.

The showroom, which is on the second floor of 80 Greene Street, above the store, in the manner of the old Parisian couture houses, is reached via worn, tilting wooden stairs--the classic artist's-loft-in-SoHo staircase. (It is so authentic-looking that it may actually be authentic, which doesn't mean that it wasn't methodically thought out by Lang.) Going up and down the stairs were young men and women in Helmut uniforms: white shirts with the armholes cut high (which narrows the silhouette), black pants, and black shoes.

Helmut Lang was dressed in Helmut Lang, too: he was wearing a light-blue button-down shirt with an HL insignia, a crew-neck T-shirt visible underneath; Helmut Lang jeans, the stiff but not lacquered kind; and his new black patent-leather Helmut Lang shoes, without socks. He walked as though he had just dismounted from a motorcycle, legs slightly apart. His dark-brown hair was long and slicked back. When he smiled, his eyes appeared friendlier than his mouth, projecting the simultaneous feeling of ease and reserve you get from his clothes. He looked healthy, even slightly voluptuous, but there was also something "broken" about him, a word once used to describe what he wanted his male models to look like--interesting in a slightly fucked-up way.

It was a blisteringly hot day, but the showroom was cool and white. The fall 2000 collection was hanging there, and editors and stylists were picking it over for items to use in photo shoots. I admired the gray wool-and-silk suits, which have an emerald shimmer when the silk catches the light. The men's clothes were more flamboyant than the women's. In the nineties, Lang dressed women like men, and earned the love of professional women everywhere. Now, like many other menswear designers, he seems to be trying to dress men like women.

The clothes exhibited certain characteristic Helmut Lang details: a fly-front coat with only one of the buttons exposed, a jean cuffed at a certain place, a strap in the back of a jacket, which is somewhat useful--it lets you hang the coat over your shoulder--but which is also an avant-garde element. At his most radical, he seems to be questioning the basics of what makes clothes clothes. There is a sense of whimsy in Lang. Last year, a padded collar that was clearly derived from those inflatable airplane headrests began showing up on some of the coats, both in the men's and the women's lines. Instead of a designer's personality being grafted onto the clothes through marketing and advertising, there is a personal voice in the clothes, expressed in these odd details and references.

I followed Lang back to the narrow business office behind the showroom. His new scent, Helmut Lang, wafted off him. The original scent was designed for a 1996 Florence Biennial project. Jenny Holzer, who created the text and images for the project, described the odor as "the smell of the morning after a passionate but difficult night." Lang's marketing director, Jonny Lichtenstein, described it as "the way a man smells right after he has had sex." When Lang's new signature scent was tested by Procter & Gamble focus groups, people reacted badly, but Lang refused to change it. That was the scent I was smelling now--flowery and buttery at the same time. Lang describes it as "on the borderline of an aftershave," and also "worn but fresh"--the olfactory equivalent of his casual clothes. Ron Perelman, the Revlon chairman, was recently spotted in the store buying five bottles.

Lang's English is pretty good, but he speaks slowly, carefully, with little emphasis. He leans forward slightly when listening, in a manner that creates a certain intimacy. I asked him about his relationship with Prada. Lang said that Patrizio Bertelli's blunt and aggressive manner, a style that charms some people and alienates others, suited him very well. "I wanted a partner and had looked for one for a long time," he said. "It was frustrating to see our influence everywhere but not to have the money to grow big enough to benefit from it. So the question was whether to expand the company on my own or go with this other company. I had always wanted to have a business partner, because I don't like doing the business. And Bertelli seemed like the right mind for me."

Why did Lang think he could get along with Prada, when Jil Sander so spectacularly could not? Though Sander made no public statement about leaving Prada, her allies put out the word that she was unable to make the quality compromises that Bertelli's marketing demands imposed on her.

"I have no problem with him," Lang said. "We get along very well. He's a very strong personality, but they have the culture. A certain quality." He said he viewed the deal as a way of hanging on to his independence, rather than selling it.

Lang didn't want to talk about the American Fashion Awards, but he was too polite not to answer a direct question about why he hadn't shown up. The idea of being thought pretentious or rude pained him. "American people don't have the fear of being exposed," he began. "In Europe, they still respect the privacy of the artist. Here, when you have success, it's like you belong to the public. And, besides, we all know that certain awards they give you because they are on your side, and other awards they give you because it's politics. But, anyway, it doesn't matter, because I do want to play the game and help the industry. "

Lang was born in Vienna in 1956. His parents divorced when he was five months old, and his sister stayed with his mother, who died some years later. Helmut was sent to live with his maternal grandparents, in Ramsau am Dachstein, a small village in the Austrian Alps. His grandfather was a shoemaker. Helmut lived in the attic of the house. (To this day, he lives only at the tops of buildings-his current residence is a duplex penthouse in NoHo.) He was lonely, and spent a lot of time up there by himself. One can feel the influence of the mountains in Lang's work, not so much in the actual outfits (although in his earliest collections the women wore what looked like lederhosen) as in the simplicity and functionalism of the design.

"In the mountains there was a very elegant way about basic necessities," Lang told me, "a great beauty in a certain way that is completely refined but not about money. Then money comes in and it gets over the top. People who grow up in the city don't have that sense of taste, they don't experience it as connected to a real life, to nature, as I did. I was really very lucky to have that experience, though I was perhaps unlucky that my parents' divorce and my mother's death made me have it."

The mountain idyll ended abruptly when Helmut was ten. His father remarried, and Helmut went back to Vienna. The next eight years were "the most unhappy period of my life," Lang has said. His stepmother forced him to wear suits and hats that had belonged to her father, a Viennese businessman. He had to wear them to school as well as around the house. Of course the suits didn't fit. "It was completely painful to have to wear these clothes," he said. "The other kids at school were dressing like hippies, but I was not allowed to wear jeans. My chance to find my style as a teen-ager, which is a very formative time, was taken away from me. I'm not completely sure, but maybe this is why I became a fashion designer. Because I was denied my own identity."

On the day Lang turned eighteen, in 1974, he told his parents he was leaving. He never saw either of them again. His father died several years ago, and he has lost track of his stepmother. When I asked if he ever thought of getting in touch with her, he said, "Why would I?" and added, "When I make a movie, it will be called 'The Stepmother.' "

After leaving home, he lived in various apartments around Vienna, doing odd jobs. "I went through a two- or three-year period when I tried every different kind of style, trying to make up for lost time, but also looking for a uniform. Some were quite eccentric, some quite normal. For a while, I was mixing denim and made-to-measure. So, for example, I would wear an embroidered jacket with jeans." Casual American clothes, Lang said, had an extraordinary allure in Austria, where they were hard to obtain. "Eventually, I found myself wanting a certain cut of T-shirt and some off-white pants that I couldn't find in Vienna, so I decided to try to make them myself. I found some fabric and took it to a seamstress and explained what I wanted her to do." A few people liked the clothes and asked him if he could make T-shirts and pants for them. "I sold eight of each. And I was really happy, because I needed the money."

Lang gradually tried making more formal clothes. After a year and a half, he hired some seamstresses and opened a made-to-measure store. "I just learned from watching what people were doing and asking how it was done. Then I would ask what would happen if you turned the fabric inside out, or if we put the pocket over here and not over here. When you haven't the formal education of fashion school, you have the freedom to ask questions others might not ask." Running his own shop, he said, "was the best school I could have had. I was immediately thrown into the problems of making clothes for real people, and learning what their bodies were really like. Also, I had to pay for my mistakes." Word spread through Vienna of this marvellous man who could make any kind of clothes you wanted. The rich discovered Helmut, and he began making opulent ball gowns for Viennese ladies. "This was in the early eighties, when people wanted to show how much money they had." He closed the shop in 1984, and showed his first ready-to-wear collection in Paris in 1986.

During this period in his life, Lang became close friends with the German artist Kurt Kocherscheidt and his wife, the photographer Elfie Semotan. He frequently stayed with them and their two young sons at their place in the Austrian countryside. When I spoke with Semotan, she said her husband's influence on Lang was in "giving Helmut a method of working. Kurt would stay up late, listen to music, fall asleep, wake up, and work again. When he wasn't working, he would try keeping his head empty. Stay free--floating on the outside, watching for things. This is what Helmut has, and it is a gift. You let things pass in front of your eyes without interfering." When Kocherscheidt died of a heart attack, in the early nineties, Lang became a kind of father figure to the boys, Semotan said. "He was just always there. I have a picture in my mind of the youngest one literally leaning up against Helmut for support."

At his early shows in Paris, Lang established an avant-garde reputation with his use of techno fabrics. He made a shirt that changed color on contact with the skin, shiny metallic pants, and a rubber dress. Angie Rubini, who worked for Lang's public-relations agent in those days, said, "He had a real buzz around him, partly because he was Austrian and all the other European designers were French and Italian. Now you see Belgians, all sorts of nationalities, but Helmut was really the first from outside the usual crowd."

The recession of 1992, which followed the grunge movement, set the stage for Helmut's minimalist style. The eighties had been about showing money; the nineties were about hiding the money. Lang's secretive aspect perfectly suited the Zeitgeist. Anna Wintour said recently, "Helmut came along and at first it was 'Wait a moment, what's this? This is not in the spirit of the mid-eighties,' which was all about opulence. But then everything crashed and fashion reflected that, and Helmut was there to take advantage."

By 1997, when Lang moved to New York, he was at a crossroads. The press loved him, his influence was everywhere. In launching his jeans line, in 1997, Lang more or less single-handedly rescued denim from the fashion wilderness. His dirty denim jeans of three years ago are now being copied by cK and SilverTab, a Levi's brand; his paint-spattered jeans have been knocked off by Banana Republic; and his raw denim is everywhere. Lacking the money to capitalize on his success, he had to watch as other designers appropriated his ideas for the mass market. "The amount of copying that goes on is outrageous," he said. "It isn't just our clothes--it is every part of our identity. The other day, I was in a cab and I saw a bag on the street and thought it was one of our bags, and then I saw another designer's name on it." A designer in this situation has three choices: he can take the company public, he can license his name to other manufacturers, or he can go into a partnership with an investor. At one time, Lang almost accepted an offer to be the head designer for the house of Balenciaga, once run by the famous Spanish couturier CristÛbal Balenciaga. But ultimately he decided on the joint venture with Prada.

There is a certain logic to Lang's Prada deal, but it also seems risky for him. Prada cultivates a style similar to Helmut Lang's--classic clothes, luxury sportswear, cutting-edge techno fabrics, and a love of uniforms--and their respective styles are getting closer all the time. Indeed, Prada seems to have already helped itself to a large portion of Helmut Lang's stripped-down aesthetic (Prada Sport is particularly Lang-like), and now that he's part of the family his innovations will be even more available. In a growing number of cases, the only significant difference between Lang's clothes and Prada's clothes is the price--Prada is more expensive, and this season Helmut Lang prices appear to have dropped by about twenty per cent across the board. This suggests that Helmut Lang could become an entry-level branch of Prada.

To better understand how Helmut Lang fits into the growing Prada empire, I met with Giacomo Santucci, a courtly man with close-cropped hair, who is the managing director of Helmut Lang. We met in a palatial town house just outside the center of Milan, which is serving as the showroom and temporary headquarters for Helmut Lang in Italy while more contemporary, loft-style headquarters are constructed. Santucci's office was almost empty of furniture, and the walls had been painted white. Space is an important part of Prada's image of luxury, and there is a lot of it around Prada offices and stores. As Santucci explained, at the time that Prada began to establish itself as a brand, in the eighties, the luxury stores were cluttered with goods. "There was wood, gold, brass in these stores," he said. "Prada understood that the shops actually had to look empty, with only a few products on display, to give more space and freedom to the individual shopper."

Prada, founded in 1913 by the grandfather of Miuccia Prada, originally made bespoke steamer trunks. Today, the Prada Group, like its two closest rivals, the luxury conglomerates LVMH and the Gucci Group, is a fashion company based on an accessories company. As Faye Landes, of Sanford C. Bernstein, explained to me, Wall Street likes these types of fashion businesses because cash flow is supplied by a regular sale of accessories rather than by the more erratic sale of clothes. "And it doesn't matter what size your body is," she said. "Anybody can buy a piece of the image of Prada by buying a bag." The clothes are like accessories for the accessories: at Prada, the brand sells the clothes, and not the other way around.

Such a business would not be possible without complete control of the Prada image, Santucci told me. The top two buttons of his Prada suit were buttoned, giving him the snug, vaguely militaristic look of the Prada man. (Around Prada, it's hard to tell the executives from the security force.) He paused to sip his espresso, dabbed his lips with a napkin, and continued: "If you look at the fashion business now, it is more about being a creative director than a designer. Prada didn't consider buying Jean Paul Gaultier, for example. He is an incredible designer, but if we had to be his partner we could not bring that much to the work, because we don't have the skills to manage that kind of work. We looked for brands that were very much in tune with our spirit."

In doing so, Prada is changing the meaning of the individual designer's role in creating fashion. "Before, the notion of creativity was linked to a designer, a designer with a very clear point of view," Santucci said. "Armani is definitely a designer. What he did twenty years ago he is doing now. He is very consistent. At Prada, the designer's role has evolved."

Lang had told me he had complete control over the image of Helmut Lang, but, listening to Santucci, it didn't sound that way. "Image is all-important to the marketing side, because it is something you can control," Santucci said. "Image is control. Image is not totally creative--it is also managerial." It seems as if the very attribute that makes Helmut Lang's image innovative and appealing, which is the separation between the man and the brand, also makes that image easier for Prada to control.

If there is any doubt about the diminished role of the individual designer in Prada's concept of fashion, it was dispelled at this year's spring-summer men's shows in Milan. In a press conference that Patrizio Bertelli gave right before the Jil Sander show, he said that he did not intend to hire another designer to replace Sander. "We are not looking for a designer, neither for the women's line nor the men's line. What's needed now in the fashion world is the role of art director, which is what Tom Ford does for Gucci." He added, "Tom Ford is not a real designer. He's just good at marketing. He's not like Karl Lagerfeld, who wakes up in the morning and sketches a dress." (In Women's Wear Daily a few days later, Tom Ford said, "Happily, I have never had the misfortune of waking up next to Patrizio Bertelli, so I haven't any clue how he knows what I do first thing in the morning.") When Bertelli was asked by Suzy Menkes, of the International Herald Tribune, what his wife's role was, art director or designer, he answered, "Miuccia I'd put somewhere in between." Menkes concluded by claiming that this development represented the end of fashion's "paternalistic structure for something more ruthless."

Back in New York, I asked Lang what he thought of Bertelli's comments. He said he did not take them very seriously, explaining that Bertelli liked to make outrageous statements to generate the press's interest. "You cannot replace the real person behind the name with a team and get the same result," Lang told me. "You can replace it and it might go on as before. It might be better able to fulfill the marketing goals without the artistic goals to stand in the way. But you could never go on with my personal voice if I was no longer here, no." Lang's slight smile seemed smaller and tighter than usual. "My personal voice cannot be replaced by a design group."

On a sultry day in August, the usual collection of people was hovering outside the second-floor showroom, all waiting for their right organic moment. Inside, Helmut Lang was supervising a fitting for a friend who was getting married the next day. He wore a tight, mottled gray T-shirt, his usual jeans, no socks, and the patent-leather shoes. The bridegroom and his best man were wearing white suits. Lang looked intently at the pant leg of the groom and instructed one of his assistants to pin it a little higher. The groom's hair was plastered at odd angles. He looked "broken" in the Helmut Lang mode. When Lang finished, he kissed the groom on the cheek and joined me.

I followed him across the street, to look at what will be the new perfumery. The store will eventually have a laboratory, where people will be able to personalize their own scents by blending different oils, and a sales floor above, where items like toothbrushes and soaps will be sold along with the perfumes.

Pointing up Greene Street, Lang explained that his design studio would be moving a block north, to a space above the PaceWildenstein Gallery, later this fall, and that his press office would expand and take over the current building. He is also thinking of opening a made-to-measure store. There were some Con Ed workers up the street, wearing the orange safety vests that Lang made into a motif in several of his late-nineties collections. Once you had seen these vests in the store, you could not look at them on Con Ed workers without thinking of the orange in a fashion context--not necessarily a good thing. I was wearing a pair of Helmut Lang cargo pants that were several years old. Other designers' clothes often seem dated after a season or two, but not Lang's. In a sense, Helmut Lang has solved the problem of what to wear too well for his own good: when you've got a couple of his uniforms, you don't need to buy any more clothes.

Lots of people were around, but no one recognized Lang--the man dressed in T-shirt and jeans, describing his big plans for the neighborhood. He had told me earlier that what he likes about New York is that you can be at the center of things and still live as though you were in a village. Seeing him standing in the midst of his growing empire-the burgher of SoHo--it was as if he were rebuilding the Alpine village of his boyhood. I repeated something Louise Bourgeois had said about him: that he liked New York because he was a runaway. "But I don't feel like I'm a runaway anymore," he said. "I'm home."

Copyright © John Seabrook 2003. All rights reserved